What International Children's Literature Offers

The following is a speech Jessica Powers, our Editorial and Foreign Rights Director, gave at the 2019 Neustadt Children's Literature Conference.

Two weeks ago, I returned from a six-week trip in South Africa with my 13 year old niece. My niece has not traveled a lot and she had never been outside the U.S. so this was kind of a big deal. Now, my niece is a very American teen. She’s articulate, smart, sassy, stubborn, extremely opinionated, and a bit self-centered and full of herself. She’s interested in typically American things: she’s in love with the musicals Hamilton and Be More Chill, both which she can quote and sing by heart; she’s devoted to anime; and she listens to music like “Heavy Dirty Soul” by 21 Pilots. So...When I go to South Africa, I do not travel in hotels or go on safari. Thirteen years ago, an Ndebele family in Johannesburg emotionally adopted me as a member of their clan, so my niece was getting herself into something the likes of which she had never seen before. From the airport on, she was immersed in the daily life of an African family. She had to eat pap and boerwors. She cuddled my 2 month old niece, born on my birthday, which according to African custom makes her my twin even though we are 45 years apart in age. She danced in the streets of Alexandra township with my African nieces and their friends; they all twerked together and they tried to teach her how to do Zulu dancing. While we were there, we participated in lobola (brideprice) negotiations for my Ndebele brother to marry a young Sotho woman; my niece participated in helping to buy the sheep and slaughter it as part of the ceremonies. She was a participant in the women’s ribald singing and dancing as they brought the bride to the groom’s house.

I have to tell you the truth though. After my niece’s first night in Africa, I worried how she would fit in. I worried because she talked non-stop from the airport to my sister’s house, and every word out of her mouth was about herself and her life in America. My African nieces, who are fourteen and fifteen, are lovely and typical of African young women. They don’t assert themselves, they are quiet and respectful. My heart sunk as I watched this American teen and these African teens interact and my American niece dominated my African nieces with her chatter and self-assurance and pure American-ness. Fortunately, that was just the first night, and things got better. Only a few weeks later, I was lucky enough to overhear her describing her trip so far to her parents. I had to laugh when she said, “You just have to hug everybody. I mean, that’s how they greet people here. And when we’re driving around, people wave at us. Everybody is so friendly! Do you know, one of the things I’ve realized after being here is that Americans are very rude? We are, we are so rude and so unfriendly!”

I was glad to see that a few weeks in another country had caused my niece to be a little more self-aware of her own culture and background, of the behavior of her fellow Americans. Now I’m not sure I completely agree with her assessment of American society, but I do think one of the characteristics of American society is a tendency to think of ourselves as exceptional; to believe that both our strengths and weaknesses are unique to our historical and cultural reality. This hubris causes us to look only to ourselves as repositories of potential solutions to our problems, and to ourselves to perpetuate our strengths.

What is true of our culture is, unfortunately, replicated in the literary world.

Earlier this year, I wrote an essay on why I think it’s important for American children and young adults to read global literature. I argued that reading books by people completely outside our culture could help us gain a better perspective on our own. The editor rejected the essay and commented that Americans can gain diverse perspectives by reading the work of American writers from diverse backgrounds. She had missed my main point. American writers from diverse ethnic groups still share a fundamental point of reference: American culture and daily life. They can’t offer what international children’s literature—that is, literature written by people who live and experience life completely outside of the American milieu—can offer us. That is what I want to talk about today.

1.

My first point is that international children’s literature can help all of us begin to see ourselves as global citizens, sharing concerns with people from every nation on earth.

In the USA today, surrounded by news that focuses almost entirely on U.S. issues, watching American television and films, studying primarily American history in school, and reading American authors writing about American kids, it’s easy for American children and teenagers to imagine themselves as existing in isolation from the rest of the world. Or not even to think about the rest of the world at all! But reading books about other people in other places helps us see ourselves as part of the interconnected and dependent and beautiful system called humanity. Like animals of the oceans, we may occupy different ecosystems but we are part of the same fundamental environment. Changes in one ocean have reverberations and profound effects for sea creatures living in other oceans. So too for humans. American kids are connected to the people of Hong Kong, even if they don’t realize it or even know that Hong Kong is a place. What is happening there matters, not just because of some abstract ethical value we might espouse about the interconnectedness of humanity but because what is happening there now will quite literally change the lives we and our children lead.

I grew up in El Paso, Texas, 3 miles from the Mexican border. As a child, I was immersed in the rhythms and rituals and values of Mexican culture. I’ve never taken for granted the primacy of mainstream American culture, since it was never the primary culture that surrounded me. Unfortunately for most American kids of every ethnic background, it’s easy to assume that American culture and life is the only thing that matters, because that’s the only thing they know. And to be frank, that isn’t preparing them very well for the future.

Global literature can change that.

2.

My second point is that international children’s literature allows us to escape the claustrophobia of our current social climate yet still examine the human condition including those very same issues that we face here. Sometimes, it’s easier to explore the problems that we face in our own lives if we see them embedded in a completely different context.

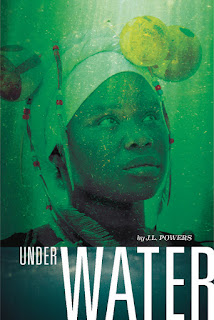

In my most recent young adult novel, Under Water, I explore the very real problem of xenophobic violence against immigrants in South Africa. My heroine Khosi speaks out against the violence; somebody murders the Somali who owns a tuck shop near her house and leaves the body on her doorstep as a message to her to shut up. When we were in South Africa just last month, mobs set Zimbabwean and Nigerian immigrants on fire and shut down the streets of neighborhoods in Pretoria and Johannesburg with violent riots. I was appearing at the South African book festival, which was literally taking place in a street adjacent to the riots. Believe me, I chose our route to the book fair very carefully and talked to my niece and my 9-year-old son about what was happening. American children and teens may not see mobs enacting violent justice against immigrants, but they do hear about incidents like the recent mass shooting in El Paso, when a white supremacist came to my hometown to enact what he saw as necessary justice against Mexican immigrants. Are the issues so different? Yet how many librarians, when trying to make sure their bookshelves are “diverse,” stop when they’ve filled the checklist of books by American writers of diverse identities set in the USA? American kids of all kinds also need windows into the worlds outside of the United States in order to become educated participants in our increasingly global democracy. They need to understand that the problems of our society are problems faced elsewhere by other people in different cultural contexts. And sometimes it’s easier to talk about and think about those problems in another society; there is less emotionally at stake for you, for the people around you.

3.

This leads to my last and third point. Like heroines who embark on a journey to a different world and then return to their own as a fundamentally changed person, reading books set in places that may seem alien to our own world can allow us to return to our own lives with a renewed vision, with alternative solutions for change, and with greater hope for healing.

In the last decade, children’s literature in the United States has seen a remarkable transformation. The diversity movement has gone viral and mainstream. It is no longer a fringe movement of small presses and backstage, whispered conversations. Concerns are still prevalent but we have seen a real sea change. My point today is that if we conceive of “diversity” as an American issue, we may inadvertently continue to perpetuate some of the ongoing cultural problems that the movement has tried to address and solve. The purpose of art is not only to create models of our disease/illness but to envision, describe, and create the medicines that can heal us. Global literature can give us perspective on American life and culture, engender a wellspring of creative thought to help us heal, and launch us into a new vision for justice and peace throughout the world.

Thank you.

Comments